Museum der Bank of England

Wenn es kein Logo gibt, wird diese Spalte einfach leer gelassen. Das Bild oben bitte löschen.

(Dieser Text wird nicht dargestellt.)

Threadneedle Street

London

EC2R 8AH

Tel: +44 (0)20 7601 5545

Die Bank of England ist offiziell unter dem Namen „Governor and Company of the Bank of England“ bekannt. Im Londoner Geschäftsviertel wird sie oft als „Old Lady of Threadneedle Street“ bezeichnet, und ihr Museum gleich um die Ecke zeigt stolz ihre Geschichte als Zentralbank des Landes und als Druckerei der Banknoten.

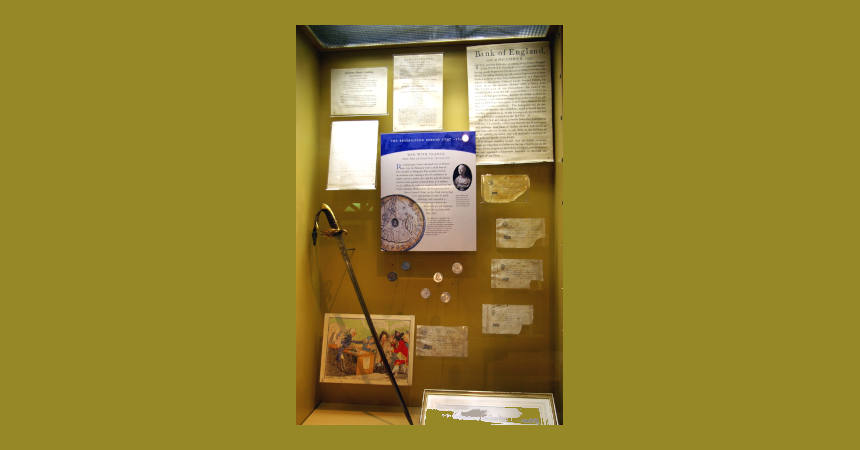

Beginn im Jahr 1694

Die Bank of England wurde von dem schottischen Kaufmann William Patterson gegründet. Ausgestellt sind Pattersons Vorschlag, die von Wilhelm III. am 27. Juli 1694 erteilte königliche Charta und das Hauptbuch, in dem die Namen derjenigen verzeichnet sind, die das Anfangskapital von 1,2 Millionen Pfund verliehen haben. Ebenfalls ausgestellt ist eine Eisentruhe aus der Zeit um 1700, der Vorläufer der modernen Tresore. Es handelt sich um das älteste Möbelstück im Besitz der Bank, das als „The Great Iron Chest in the Parlour“ bekannt ist.

Wachstum und Expansion: 1734–1797

Aus dem frühen 19. Jahrhundert ist eine undatierte 1-Million-Pfund-Note ausgestellt. Obwohl die höchste jemals von der Bank ausgegebene Stückelung 1.000 Pfund war, die 1923 auslief, wurden Banknoten über 1 Million Pfund seit dem 18. Jahrhundert nur für interne Buchhaltungszwecke verwendet.

Da die Bank ab Februar 1797 kein Gold mehr zur Verfügung hatte, hortete die Öffentlichkeit Silber, was zu einem ernsthaften Mangel an Münzen führte. Die Bank verwendete daraufhin spanische 8-Reales-Münzen, d. h. „Real de a ocho“, aus ihren Tresoren und prägte sie mit dem Kopf von Georg III. Es sind mehrere Exemplare mit den ursprünglichen ovalen und den späteren achteckigen Prägungen ausgestellt.

Ebenfalls ausgestellt ist eine 5-Pfund-Banknote vom 15. April 1793 – die älteste bekannte 5-Pfund-Banknote der Bank of England. Die 10-Pfund-Banknote, die erstmals 1759 während des Siebenjährigen Krieges aufgrund von Münzknappheit ausgegeben wurde, war bis zur Einführung der 5-Pfund-Banknote der niedrigste Nennwert.

Die Rotunde

Die Rotunde ist der zweite große Bereich des Museums. Auf einem Podium in einem geschützten, durchsichtigen Gehäuse befindet sich ein 13 Kilogramm schwerer Barren aus reinem Gold auf einem Sockel, der von mehreren Sicherheitskameras und Wachleuten überwacht wird. Eine Waage zeigt den tatsächlichen Wert des Barrens auf der Grundlage des Londoner Goldpreises des jeweiligen Tages an. Durch eine kleine Öffnung können die Besucher den Barren anfassen, so dass er mit etwas Mühe mit nur einer Hand vom Sockel gehoben werden kann. Ebenfalls ausgestellt ist ein 12-Royal-Unzen-Barren (373 g) aus 24-karätigem Gold, das so genannte „Krönungs-Barren“, den Elizabeth II. anlässlich ihrer Krönung 1953 der Westminster Abbey schenkte.

Banknoten-Galerie

In der nahe gelegenen Banknotengalerie sind eine Druckpresse und eine geometrische Drehbank aus dem Jahr 1905 zu sehen, mit der die hochkomplexen Muster für die fälschungssicheren Methoden bei der Herstellung von Banknoten und anderen Sicherheitsdokumenten erzeugt wurden. Erst 1928 führte die Bank dieses Verfahren für den Druck ihrer Banknoten ein.

Die Galerie erzählt auch von der Entstehung und Entwicklung der Banknoten und zeigt eine glänzende Stichtiefdruckplatte für die Vorderseite von 28 50-Pfund-Noten mit dem Porträt von Königin Elisabeth II.

Weitere Ausstellungsstücke sind erbeutete Originalvorlagen, Skizzen, Prägestempel und Fälschungen der 5-, 10-, 50- und 1.000-Pfund-Noten der Operation Bernhard, die von jüdischen Gefangenen des Konzentrationslagers Sachsenhausen hergestellt wurden.

Der Weg zur Dezentralisierung

In einer weiteren Galerie wird die historische Umstellung Großbritanniens auf das Dezimalsystem in den 1960er Jahren nachgezeichnet. Das jahrhundertealte Währungssystem Pfund-Schilling-Pence aus angelsächsischer Zeit wurde durch eine Dezimalwährung ersetzt, bei der das Pfund nun in 100 Pence unterteilt ist.

Vor dem Buchladen in der Haupthalle ist eine Ausstellung von Münzen zu sehen, die von der Königlichen Münzprägestätte geprägt wurden. Sie wurde 1932 mit dem Ziel eingerichtet, eine repräsentative Sammlung britischer königlicher Münzen zusammenzustellen, d. h. der Münzen mit dem Porträt des regierenden Monarchen, die seit 1694, dem Jahr der Gründung der Bank, ausgegeben wurden.

Dieser Text wurde von Howard M. Berlin geschrieben und erstmals in seinem Buch The Numismatourist im Jahr 2014 veröffentlicht.