Money Museum of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago

Wenn es kein Logo gibt, wird diese Spalte einfach leer gelassen. Das Bild oben bitte löschen.

(Dieser Text wird nicht dargestellt.)

230 South LaSalle Street

Chicago, IL 60604

Phone: +1 (312) 322-2400

Opening hours:

Mo-Fr 10 am – 5 pm

Chicago is home to the head of the Federal Reserve Bank’s Seventh District. Visiting the Money Museum can be done either with a guided tour or on your own. The guided tour lasts about 45 minutes, starts at 1 p.m. daily, and includes a short video in the theater about the Federal Reserve System.

Story of America’s Money

The story of America’s money with appropriate specimens starts with the “Colonial America” period from 1620 to 1789, when silver and gold were the money of choice, but they were also in short supply and bartering was a common practice.

The next period, “Experiments In Banking 1789-1860,” was the period between the Revolutionary and Civil Wars when the government went through a trial and error period of developing its financial system. It twice tried unsuccessfully to establish a central bank. In its place, up to 10,000 private state-chartered banks filled the void.

“Financing a Civil War 1860-1865″ is next when the banking legislation of the 1860s provided for the national banking system and a uniform currency. The National Banking Act of 1863 created a system of federally-chartered but privately-owned banks to issue a national currency primarily backed by government bonds.

On display is an 1861 $10-demand note, called a “greenback” because of the green color on the reverse, which began the tradition of printing money in green ink on a cotton-linen paper blend.

Following the Civil War, “An Era of Silver and Gold 1865-1900” was the period of tight money. The major issue was how much money should be created and how it should be backed. Some wanted gold as the best means to stabilize the economy; others wanted silver to be used to raise prices and wages.

Federal Reserve Notes

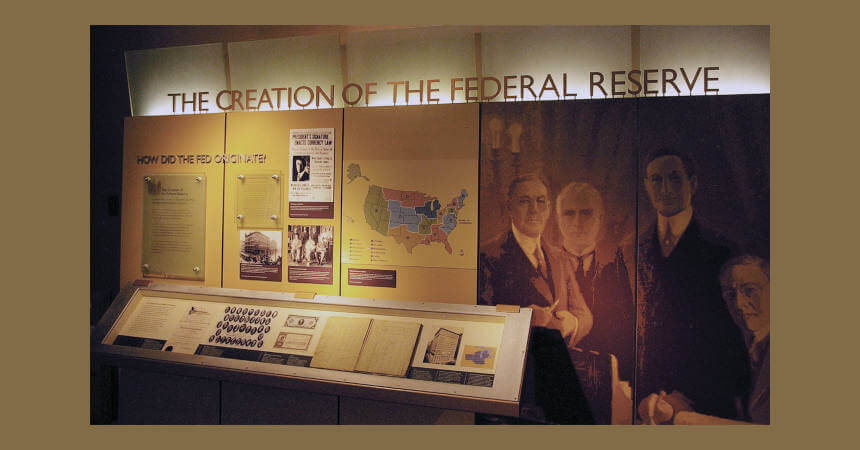

A New Central Bank 1900-1918″ is the era of the creation of the Federal Reserve System in 1913. A new currency appeared for the first time-the Federal Reserve Note (Series of 1914). Among those shown are the 1918 $5,000- and $10,000-Federal Reserve Notes.

The “Depression and War 1918-1945” period has the nation dropping the gold standard in 1933 and coming out of the depression. The Fed assumed the primary responsibility for influencing the supply of money in the economy.

Other Notes on Display

One section of the Museum has a display titled, “Money in America,” whereby a number of the more interesting examples of America’s currency are showcased. Included are: an 1875 $2-National Banknote, aka the “Lazy Two”; an 1875 $10-U.S. note-aka the “Jackass note”; a 1901 $10-U.S. note-aka the “Bison note”; the back of an 1890 $1,000-U.S. Treasury note-aka the “Grand Watermelon”; and a 1905 $20-Gold Certificate-aka the “Technicolor” note.

Know Your Money: Find the Fake

The paper money contains various security features, to help prevent it from being copied: a large portrait, watermark, security thread, fine line printing patterns, microprinting, and color-shifting ink. However, that still hasn’t stopped those from trying to counterfeit the nation’s currency.

There are specimens of $5-, $10-, $20-, $50-, and $100-notes where the face side of each is shown and you have try to decide if that note is genuine or counterfeit.

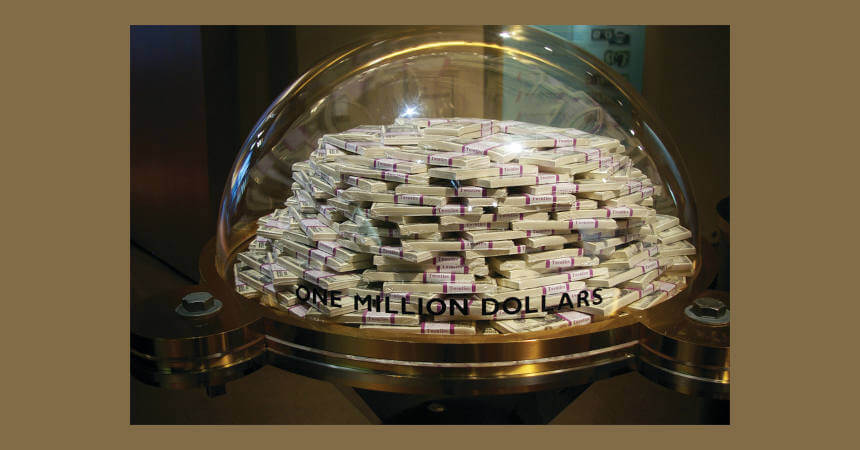

One Million Dollar Displays

There are three $1-million displays. One is a $1-million cube made up of $1-bills that weighs over 2,000 pounds. Another display has a suitcase filled with 10,000 $100-bills. With a 10-second time delay after pushing a button, visitors can have their picture taken as a free souvenir standing next to the suitcase with the $1 million!

This text was written by Howard M. Berlin and first published in his book The Numismatourist in 2014.

You can order his numismatic guidebook at Amazon.

Howard M. Berlin has his own website.